I was planning to write this weeks ago, before the advent of ChatGPT-4. Now, with each passing day, my piece is rapidly losing any semblance of prescience, so I figured I’d better hammer it out tonight.

The latest iteration of artificial intelligence, championed by ChatGPT-3, has been made public for some months now. Pretty much anyone who tried it was initially impressed, but many proceeded to find it lacking in substance. Just among blogs that I actively follow, we have Brett Devereux (historian) saying the (then) current generation of AI will not meaningfully impact academia. Then there is Scott Aaronson (complexity theorist) fervently defending the potential of AI from doubters of its capabilities.

They are both, in their way, correct. For my part, I do not know what positive use cases may exist for AI, and I especially don’t know whether Large Language Models are ever going to be a path towards true human-like intelligence or a mere deadend. What I do believe with some confidence is that even as it exists today, AI heralds a big problem, and it comes to us long before the threat of Skynet or Roko’s basilisk yet looms over the horizon. ChatGPT spells the end for discourse on the internet.

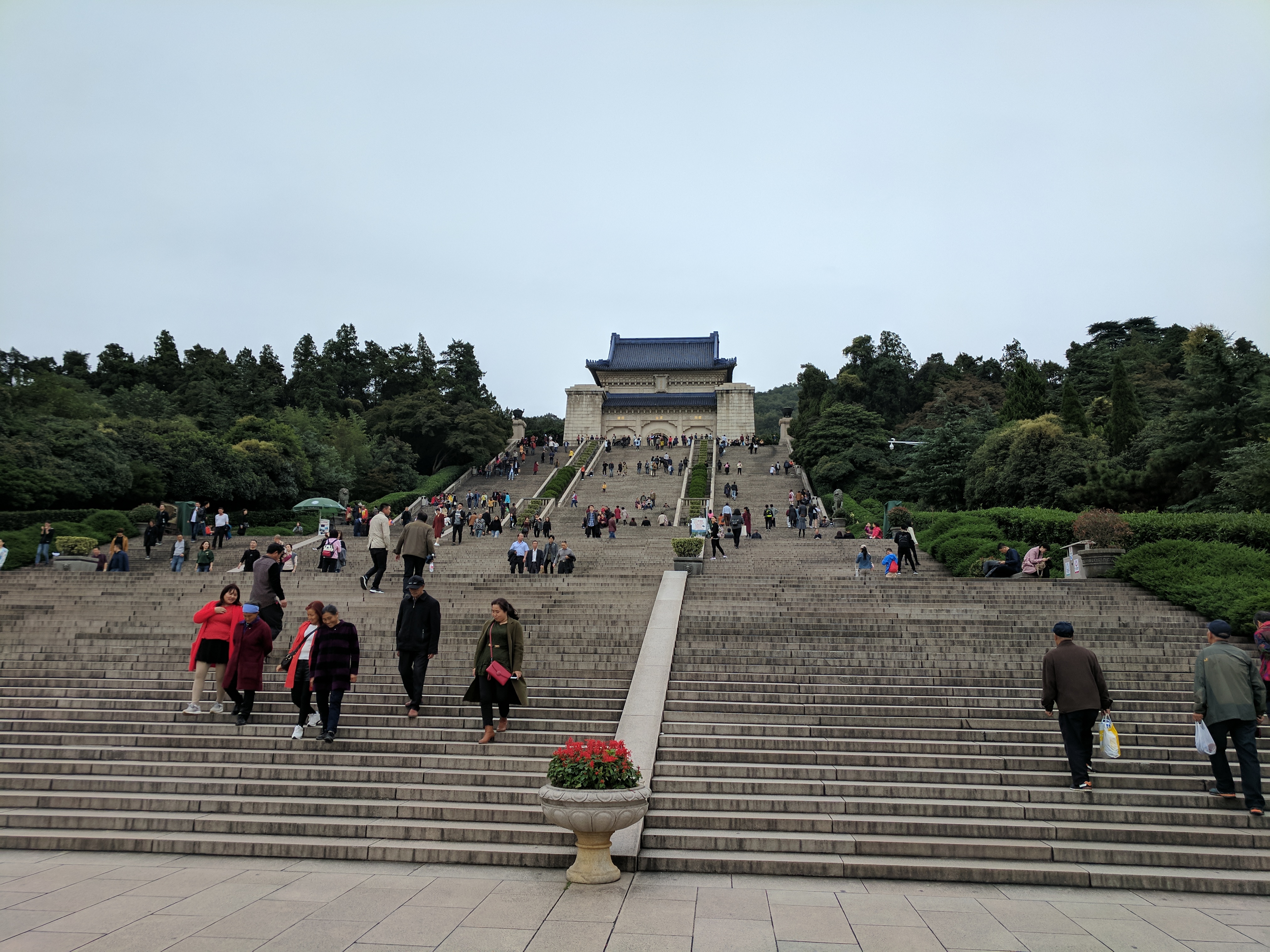

In order to expand on what I mean, let me use a current event as an example: the ongoing protests in Paris. As it happens, I am writing this from Paris right now, where I am spending the weekend. I have not seen much signs of actual disturbance, mostly because Europeans take everything easy on Sundays, even la Manifestation, but the ample amount of piled up garbage is testament enough to the impact on the city.

So regarding this protest, in the discussions I’ve read about it online, I’ve seen all of the following points made:

- That these protests are a great representation of the French people asserting their will, in a way Americans and other countries do far too rarely

- That the French are lazy bums who strike on a whim, even for something as benign as raising the retirement age to 64, still among the lowest of such age restrictions in the world

- That raising the retirement is a mandatory course any realist must take, because there is no possibility for the current system to be economically sustainable, with the shifting of demographics due to longer lifespans and lower birth rates

- That this is a lie, the system is perfectly sustainable accounting for X, Y, and Z

- That this is true, but punishing the working class when wealth inequality is so high is unacceptable, and taxes should instead be levied on the 1%

- That his has been tried before, but failed because the wealthy taxbase will simply relocate themselves or hide their assets

- That this in turn is a lie, spread by the same corporate lobbyists who profit from your believing it

- That his has been tried before, but failed because the wealthy taxbase will simply relocate themselves or hide their assets

- That Macron did this by sidestepping a vote by parliament, a betrayal of democracy that marks France’s descent into tyranny

- That Macron used a mechanism in the constitution that has been deliberately designed for this purpose, is entirely legal, and has been used frequently for similar purposes

- That Macron used the mechanism only after knowing parliament would vote against it, and so is betraying the principles of democracy regardless

- That Macron, who was only recently and fairly elected, with the raising of retirement age as part of his campaign promise, could in no way be accused of breaking with democracy

- That Macron used the mechanism only after knowing parliament would vote against it, and so is betraying the principles of democracy regardless

- That Macron used a mechanism in the constitution that has been deliberately designed for this purpose, is entirely legal, and has been used frequently for similar purposes

- That the protests have all been peaceful, but the police have turned to violence because they are not defenders of the public, but rather enforcers for the ones who pay them

- That the protests were the first ones to start looting and set fires, whereas the police are doing their duties to protect the properties of citizens

- etc etc…

Now some of these points are factually incorect (logically at least a few must be since they contradict each other), others are simply things one might disagree with. I do not bring them up here to express any personal opinion on this matter, but simply to say that I have seen every one of these points made by at least one online personan who seemed reasonable, cogent, and genuine in their belief of their expressed opinion.

And I was reasonably sure none of them were AI.

And that means there’s some value in the discussion, since if there is any point to discussing politics on the internet, it’s to see what others think. We may fall into traps of our own making, get caught up in biases or only engage with our own isolated bubbles, but if we are careful it is at least possible for us to hear from someone we don’t agree with, and learn something.

Now you may object to this assertion outright. You may say that anyone who takes anything online with any credibility is a fool. The only source for facts are the primary, and the only correct opinions come from <insert authority figure of choice>. Before you have finished getting a degree in sociology or political science, and read the whole corpus of Marx/Locke/Wittgenstein, you shouldn’t have a political opinion at all.

Even if I agreed with that in principle, it doesn’t matter because that’s not how political discourse happens in the real world, and that’s not how people become politically aware, and so that’s not what affects how people vote and who gets elected.

So now the question is, if an actor, with the resources of a government or large corporation, could benefit from controlling that discourse, why wouldn’t they? Already, propaganda and astroturfing are the most harmful things to the health of the internet, but at least today if it’s done by bots then it is noticeable, and if it’s done by people that still accounts for a minority of opinions found online. With the power of LLMs, there is absolutely no reason why this wouldn’t become the overwhelmingly dominant form of online speech, to the point that soon you should doubt you could have a conversation with a real human on an anonymous forum at all.

I don’t really see any solutions that could mitigate this. I certainly don’t think it’s possible to contain AI through legal repression now that it’s out of the box (that has never worked). For a brief while, there was talk that AI generated content could somehow be detected algorthimically or through some special signature. That was always obvious to me to be a vacant hope: the whole point of these things is that they emulate human speech, a job they will get exponentially better at. And even if OpenAI can be convinced to rein ChatGPT in with some watermark, there is certainly no reason a malevolent actor using some clone of it has to. Lastly, if we try to enforce the authenticity of online content through some kind of mass censorship and/or surveillance/vetting of the publisher, that will nevertheless destroy the web as we know it.

And of course, this isn’t just about politics. For the time being, we might hope we have some measures that could guarantee the sanctity of absolute truths online, say the formulation of Euler’s identity, or the exact words of the Gettysburg Address. But anything that is subject to any kind of subjective opinion is doomed, whether it is about which movie deserves credit for its introspective take on nihilism in the multiverse, or which restaurant serves a dish best with regards to authenticity and deliciousness. The whole point of conversation would be removed, and all that could remain is content fit for consumption (which one hopes might be manmade, until TarantinoGPT comes along…).

Now this is a lot of doom and gloom, especially for me who usually has the more moderate takes on things. Indeed, this is a rare occurence where I find myself on the fringe but am very certain of my own position. I make no claims to be the originator of these ideas, but the majority stance among experts seems to be to acknowledge the problem, but in a much more relaxed way as a thing to watch out for eventually. To me the scenario is imminent.

If there’s any situation for the impact to this to be remotely less severe than it sounds, the only one I can think of is for the Futurists to be right – for AI to be so revolutionary in other ways that it produces a paradigm shift at least as disruptive as the internet and smartphones were for my generation. In that case, maybe even the death of discourse is not going to be the topmost issue on anyone’s mind. I don’t know whether that possibility is something to hope for or dread.